The Pearl Incident – An Indelible Part of the Wharf’s History

This month, we commemorate the 175th anniversary of The Pearl Incident, the largest known attempted slave escape, which took place, in part, at DC’s SW waterfront around this date in 1848.

This month, we commemorate the 175th anniversary of The Pearl Incident, the largest known attempted slave escape, which took place, in part, at DC’s SW waterfront around this date in 1848.

While the District Wharf, which opened in October 2017, represents a reimagined SW waterfront, the area has been home to boating and commerce for hundreds of years. For example, the Municipal Fish Market, which opened in 1805, is the oldest continuously operating fish market in the U.S. During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln, would greet wounded troops as they arrived at the Wharf on paddle steamships.

And, in 1848, there is the story of what is known as The Pearl Incident.

It was the largest recorded attempted slave escape and it took place right here at The Wharf on a 65-foot schooner called The Pearl. On April 15, 1848, 77 slaves from Washington City, Georgetown, and Alexandria boarded the ship near 7th Street SW in hopes of making a 250-mile cruise to freedom in New Jersey. While it did not end well, the incident inspired at least two notable efforts to end slavery, one by Abraham Lincoln, and the other by Harriet Beecher Stowe.

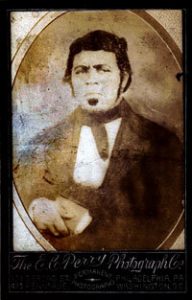

Paul Jennings

The escape attempt combined the coordination and planning of several individuals including two freed slaves, Paul Jennings and Paul Edmondson. Jennings had been a slave to President James Madison and was active in DC’s anti-slavery movement. Jennings was free but his wife was not, and by law, that meant their 14 children remained enslaved. They lived on a farm in Montgomery County which is today the site of Leisure World retirement community, according to the Sandy Spring Slave Museum.

Jennings and Edmondson plotted the escape with the help of Daniel Drayton, who the previous year had helped a slave family escape DC by boat to Frenchtown, NJ. For the larger escape, Drayton chartered The Pearl, which was owned and captained by Edward Sayres.

It was a rainy April night when slaves throughout the area made their way down 7th Street SW and on to The Pearl. One slave arrived at the ship in the trunk of a taxi which was driven by Judson Diggs, a freed slave. According to a 1998 recounting of the night’s events published in The Washington Post, Diggs was upset that the escapee he transported to the ship had no money. But he also knew Paul Edmondson’s daughter, Emily, was onboard. Diggs was in love with Emily and even proposed marriage, which was reportedly met with “laughter” and “distaste.”

The escape route was clear. The Pearl would depart the Wharf and head 100 miles south down the Potomac River to the Chesapeake Bay, then head up the bay another 120 miles, along the Delaware River to New Jersey.

Under the cover of night, The Pearl departed the Wharf and eventually made it to Point Lookout at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Unfavorable winds and tides forced The Pearl to drop anchor and wait until the weather improved.

Under the cover of night, The Pearl departed the Wharf and eventually made it to Point Lookout at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Unfavorable winds and tides forced The Pearl to drop anchor and wait until the weather improved.

As morning dawned the next day, a posse hired by enraged slaveholders, was assembled to find and recapture the 77 slaves. They were tipped off by none other than cab driver, Judson Diggs. The posse boarded a steam ship named The Salem and headed down river eventually spotting and capturing The Pearl in Cornfield Harbor near Point Lookout.

The Pearl was towed back to DC where the slaves, Drayton, Captain Sayres, and his first mate, were paraded in lock and chain through the streets of DC before angry pro-slavery mobs.

Many of the slaves were sold to plantations in the deep south. Meanwhile Drayton and Sayers were charged with 77 counts of theft and 77 counts of illegal transportation of slaves. Interestingly, they were prosecuted by Philip Barton Key, U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia who was the son of Francis Scott Key, who wrote the words and music of the national anthem.

Tensions ran high in DC as rioting engulfed the city for several days between abolitionists and those in favor of slavery. The incident, however, may have led to progress. A year later in 1849, a congressman from Illinois named Abraham Lincoln introduced legislation, albeit unsuccessful, for the compensated emancipation of slaves in the District. Lincoln did not give up. Thirteen years later, on April 16, 1862, President Lincoln signed legislation freeing slaves in the District, the first freed by federal law. Emancipation Day continues to be celebrated in DC every year on April 16.

The incident was also cited in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1853. The book was a companion to her 1852 publication, Uncle Tom’s Cabin that shined a light on the evils of slavery and eventually helped to end it.

Pearl Street, the heart of the District Wharf, is much more than just a name. It’s a nod to one of the most important incidents in American history.

If you want to learn more about the Pearl Incident you can register to attend “Remember the Pearl: 175th Anniversary of the Historic 1848 Attempted Escape” on Saturday April 15 from 2-5pm at Westminster Presbyterian Church. Reserve tickets.

This story was initially published on an earlier date.

Visitors to the Wharf will notice at the center of the neighborhood is Pearl Street, which is appropriately located parallel to 7th Street SW, from where The Pearl was launched and includes a historic marker mounted in the bricks of Wharf Street commemorating the largest recorded slave escape.

The Pearl Incident Photo Gallery

- A sculpture of the Edmondson sisters is located at1701 Duke St, Alexandria, VA

- This daguerreotype photograph shows Mary Edmonson (standing) and Emily Edmonson (seated), shortly after they were freed in 1848. -Wikipedia

- Captain Daniel Drayton

- View of 7th Street Wharf

- Approximate rendition of The Pearl

- Emancipation Day

- DC riots, call for peace

Editor’s note: There are several interesting reads about the Pearl Incident including:

Escape on the Pearl: The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad – book by Mary K. Ricks

Escape on the Pearl: The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad – book by Mary K. Ricks

“Escape on The Pearl” – The Washington Post

Failed Escape Sheds New Light on D.C. Slavery, NPR book review

How a ‘Judas’ foiled America’s largest escape attempt of 77 slaves in 1848 – Face2FaceAfrica

The Largest Attempted Slave Escape in American History – The History Channel